|

|||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

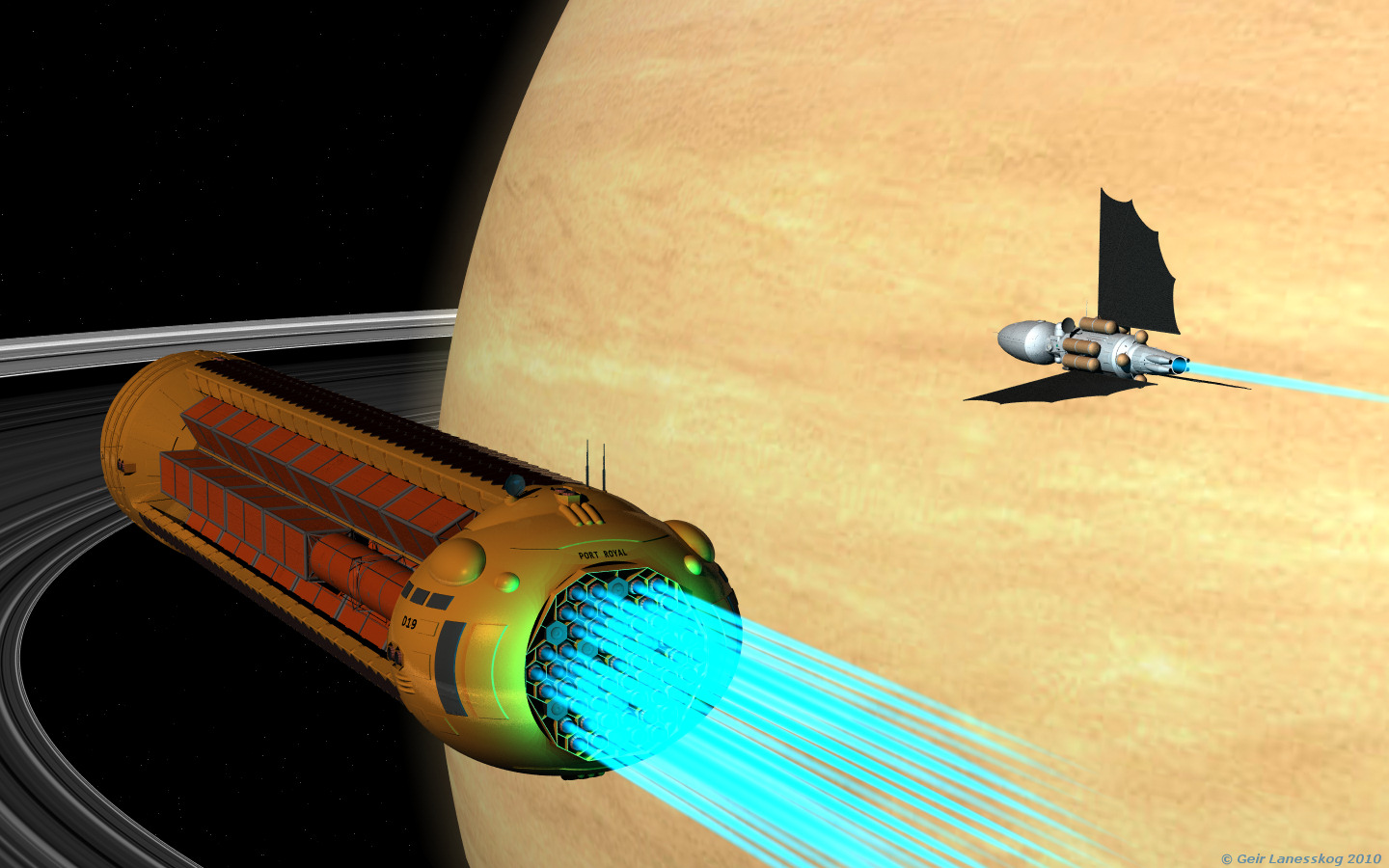

Saturn Arrival

In the early twenty-second, hauling cargo to the outer system was particularly expensive. For one thing, low velocity ships required months of travel time. Taking into account time for cargo transfer and maintenance it was a full year to Saturn and back. At that flight rate, it's hard to pay back the cost of a freighter. Worse, the colonists on Titan and the other moons didn't exactly produce a lot of goods for export. On average, a colonist took about 50-100 tons to establish and another ton a year to supply, so there was a lot of tonnage going out, and nothing coming in.

Few ships made the trip. That alone kept up the prices, but it required big ships. Freight was packed in deep space canisters, each containing 18 FEU, or standard forty-foot containers, stacked two by three by three into a hardened space-proof vault. That amounted to between five and eight hundred tons net cargo per canister. Giant two thousand cubic meter tanks held liquid or gaseous materials.

To cut costs, the freighters used water for propellant. On a Port class heavy freighter, forty-nine primary multiphase microwave thrusters accelerated steam at a few hundred thousand meters per second to provide velocity. Using water for propellant was the only way to make money on the Jupiter and Saturn runs. At the outer stop, the freighter would take on enough water for a complete round trip, saving the cost and effort of providing propellant for the next trip out.

In the second and third decades of the twenty-second century, only two large ships, the Dorado Space Industries Port Royal and Tortuga, regularly made the Saturn freight run. In addition to forty-two attachments for canisters or tanks, the ships could also carry up to two hundred passengers in the forward spin wheels.

The passenger wheels were generally fully loaded on both legs of the journey. Contrary to popular myth, not everyone who gained the funds, skills or patronage to emigrate off Earth stayed in space. The reality of life on cold hostile worlds, living in tubes or domes or deep tunnels where even the air is precious did not always live up to the expectations of those who sought to escape the crowded arcologies and free towns. About a third of emigrants did not adjust; of those, about half managed to scourge enough for a return trip; the other half often... well, eventually they were recycled.

The Port class ships were the last commercial interplanetary vessels to forgo lifeboats. The accepted wisdom was that it was best to stay aboard even a crippled ship when hundreds of millions of kilometers from rescue. But when the Tortuga's main reactor melted down, that belief proved fatal. A few managed to eject a cargo canister as a makeshift lifeboat, hoarding scarce air, water and food until rescue. Only one man survived the 171 days before help arrived. Recycling. After that drama, long duration lifeboats became mandatory for interplanetary ships.

--Great Big Book of Spaceships (Eight Edition), Public Information ePress, 2180

All pages and images ©1999 - 2010

by Geir Lanesskog, All Rights Reserved

Usage Policy

![]()